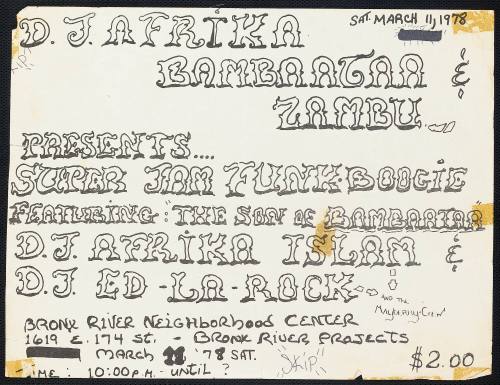

D J Afrika Bambaataa and Zambu Presents Super Jam Funkboogie at the Bronx River Neighborhood Center, March 11, 1978

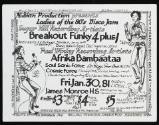

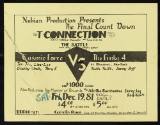

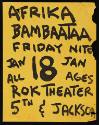

Party flyers were a staple in the early years of Hip-Hop and hard-copy invitations were the main medium for communicating information and promoting an event. The flyers symbolized many key appearances, acts, conventions, DJ performances, and contests in the Hip-Hop scene. Many flyers were created by local graffiti artists such as Buddy Esquire and Phase 2. The flyers were often presented by Hip-Hop promoters, DJs, and MCs who hosted the parties. Money was given to the artist to draw creative art and graphics for about $40-$60 for approximately 1,000 party flyers. The parks’ open public spaces have provided the perfect venues for park jams, impromptu dance-offs, DJ battles, and rap battles that established the sound, fashion, art, and message of Hip-Hop. Most of the Hip-Hop parties were a space for positivity where many of the Hip-Hop community could escape the realities of racism that included police brutality, drug abuse, and gang violence in their surrounding communities.

Many of the original Hip-Hop parties took place at local roller rinks, community centers, parks, and clubs. Roller rinks were an important cultural site for fun in the late 70s and 80s where adults and teens would attend roller discos and Hip-Hop parties. The space would be used as a place for DJs to spin, rappers to show their talents, and for breakers to showcase their dancing skills on the large skate floor. Community centers were another important space in the early years of Hip-Hop for youth to gather and escape their everyday life. Additionally, community centers and recreation centers were the original spaces where DJ Kool Herc would spin in his early era of DJing. The community centers such as the Bronx River Center and the PAL were usually located in the middle of the projects. But local promoters would give parties and give money back to the center for books and trips for the local kids in the community.

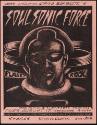

Leader of the Zulu Nation and known as one of the “Godfathers of Hip-Hop,” Afrika Bambaataa (Lance Taylor, b. 1957) is a DJ, producer, rapper, and songwriter from the Southeast Bronx. As a former gang member, Afrika Bambaataa began DJing at local parties in the early 1970s, playing Funk and Disco records but stood out as a unique and eclectic DJ because he would play records across different genres like Rock, Pop, Salsa, African, and Latin. Afrika Bambaataa also established two Rap crews: the Jazzy 5 and the Soul Sonic Force. Afrika Bambaataa crafted the foundation of Hip-Hop by establishing the five elements or five pillars: DJing, MCing, b-boying, graffiti, and knowledge. Afrika Bambaataa’s impact on Hip-Hop culture has defined the genre as a staple of creativity and expression emerging out of the Bronx.

Afrika Islam (Charles Andre Glenn b. 1967), is a Hip-Hop artist, DJ, and producer and one of the pioneers of Hip-Hop culture and the Hip-Hop radio station. He had the first Hip=Hop show on radio, Zulu Beats, WHBI - FM 105,9, in 1981. He began his musical career in 1977, joined the group Rock Steady Crew, and was an apprentice to Afrika Bambaataa. He learned the art of remixing tracks and was responsible for the events that the Zulu Nation held during the 1970s where he was the 13th b-boy of the Zulu Kings. Afrika Islam is also known for compositions that he wrote for the Soul Sonic Force and his own group called Funk Machine. For two years, he hosted the radio program Zulu Beats. In his career as a DJ, he was famous for the art of mixing on four turntables simultaneously. In 1983 he won the NMS DJ championship, Battle For World Supremacy, and in the late 80's he founded Rhyme Syndicate Records together with Ice-T.

![The Zulu Nation present their 3rd Annual Disco Tribute to James Brown: DJ Afrika Bambaataa, Zambo, MC Mr. Biggs, at Bronxriver Community Center [i.e. The Bronx River Center], Bronx, NY, November 10, 1978](/internal/media/dispatcher/411259/postagestamp)

![The Zulu Nation present their 3rd Annual Disco Tribute to Sly Stone: DJ Afrika Bambaataa, Zambo, MC Mr. Biggs, at Bronxriver Community Cente [i.e. The Bronx River Center], Bronx, NY, November 10, 1978](/internal/media/dispatcher/411257/postagestamp)